- 12.07.2023

- Kategorie Politik / Gesellschaft

Estonian General Election 2023 – a Choice Between (Mostly) Centre-right Liberalism and Far-right Populism

Guest contribution by Andres Reiljan

When launching the campaign of the Reform Party (Eesti Reformierakond, R), the incumbent Prime Minister of Estonia Kaja Kallas defined the central conflict of the upcoming election in rather stark terms: »The real choice people will have to make on 5th March is between a free and open society or an isolated and lonely angry little country.« This dramatic framing worked, as Estonians turned out in record numbers and handed a landslide victory to the ruling R, allowing Kallas to continue as Prime Minister.

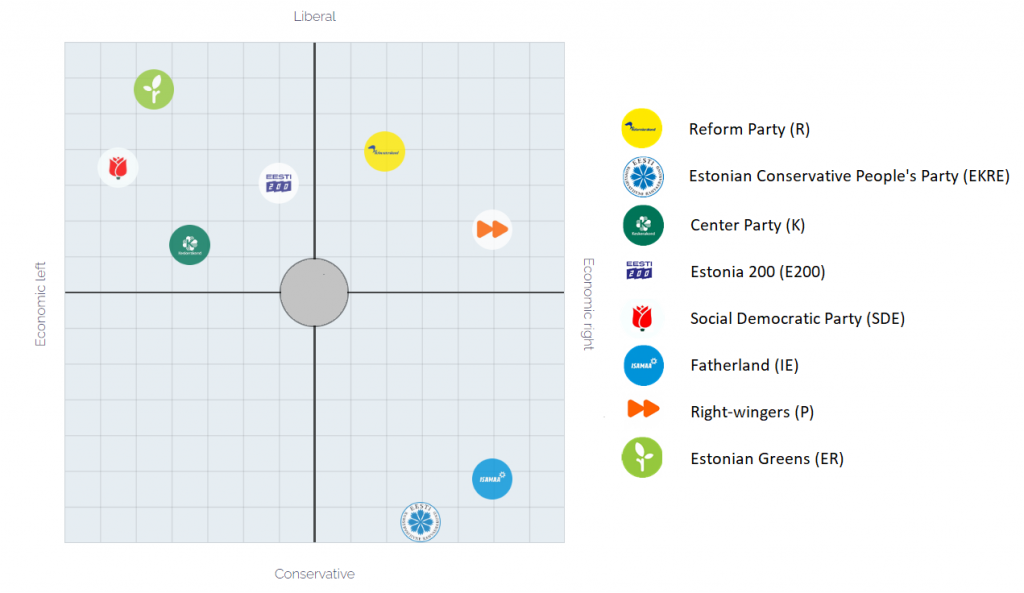

The Estonian Party Landscape and the Central Ideological Conflicts in the 2023 Election

Since its first free elections after regaining independence from the Soviet Union, Estonia has used proportional representation in its electoral system, with a 5% threshold for inclusion in parliament. This has led to a moderately fractionalized party system, with the number of parties represented in the 101-member parliament (Riigikogu) fluctuating between four and six over the last twenty years; no party has been close to achieving a parliamentary majority on its own.

The aforementioned central ideological rift has been described variously by scholars as a division over globalization, a transnational cleavage, and a value conflict between social liberals and conservatives. In terms of this divide, R represents the transnationalist liberal side that is open to further European integration, green transition, immigration, and stands for socially liberal values. R’s main contender in the 2023 election – the far-right populist Estonian Conservative People’s Party (Eesti Konservatiivne Rahvaerakond, EKRE) – has taken diametrically opposite positions: it prefers a Europe of nation states over further EU integration, wants to halt the green transition, aims to close Estonian borders for most immigrants to stop the »eradication of Estonianness«, and supports traditional conservative values. EKRE’s support had been steadily rising since it first entered parliament in 2015.

Although coalitions are not formed pre-election in Estonia, the development of some potential alliances was observable during the campaign. The most obvious allies for R in this rift over values and globalization are the Social Democratic Party (Sotsiaaldemokraatlik Erakond, SDE) and the newcomer Estonia 200 (Erakond Eesti 200, E200). While R combines social liberal transnationalist positions with a neoliberal pro-market stance on the classic economic left-right axis, SDE can be described as centre-left. E200 is a party that was created in 2018 and narrowly missed the 5% threshold in the 2019 election but has gained support since. While explicitly aligning itself with social liberal values and support for transnational co-operation like R, E200 has avoided being labelled either left or right on economic terms, instead taking a technocratic approach.

Meanwhile, EKRE’s chairman Martin Helme has been devising his own potential »conservative« coalition, with the centre-right Fatherland (Isamaa, IE) and the centre-left Centre Party (Eesti Keskerakond, K). This trio somewhat surprisingly formed a government in 2019 – then under the leadership of K – despite R winning the election. Although this government collapsed in early 2021 leaving EKRE and K in particular not on the best of terms, Helme realized that the EKRE-K-IE configuration is the only realistic option for an EKRE-led government. However, K and IE are not such straighforward allies of EKRE in terms of the ideological divide. K is not a conservative party (as indicated by its alignment with the liberal Renew group in the European Parliament), and it has traditionally represented ethnic Russian voters and the economically less well-off. As such, it makes for a rather peculiar alliance with an ethnonationalist populist party, and there have long been prominent voices within K who are against a coalition with EKRE. IE is a right-conservative party that agrees with EKRE on many value-related issues (e.g. in opposing same-sex marriage) – it has sometimes been mockingly dubbed as EKRE-light – but it has remained closer to the mainstream, largely supporting Estonia’s integrationist foreign policy line. Since summer 2022, IE had been part of the governing coalition with R and SDE.

Both K and IE have tried to avoid being too closely associated with a eurosceptic populist EKRE, but unlike R, E200 and SDE, they have not not ruled out forming a coalition with them. Thus, the central partisan conflict in this election was between the liberal wing and the right-populist EKRE, with K and IE trying to find some middle ground and keep their options open on both sides.

Figure 1. Estonian Party Landscape in 2023

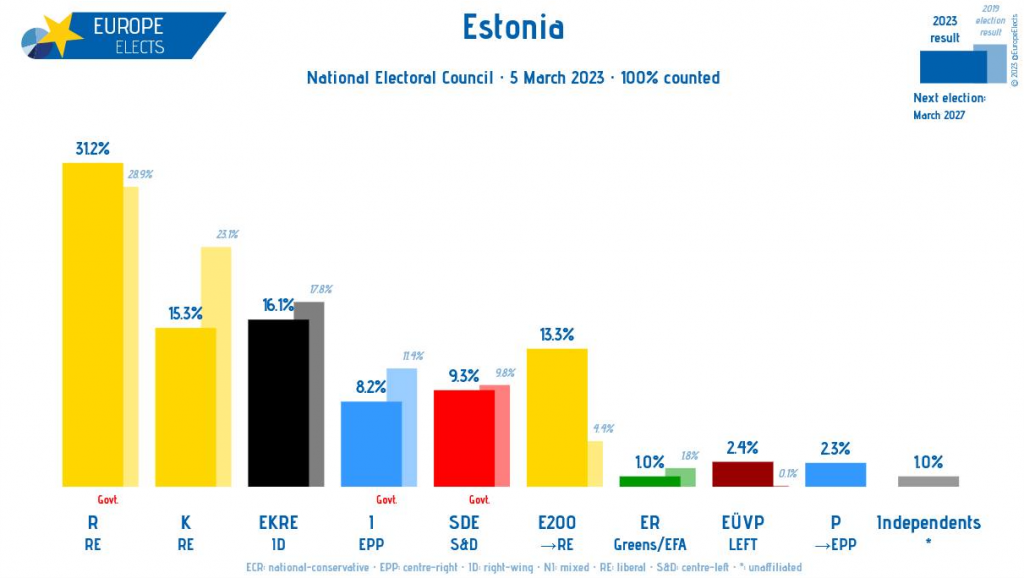

Results: The Winners and Losers of the Election

When the polls finally closed at 8 PM on 5th March 2023, an all-time high of 615 009 Estonian citizens had voted, with more than half (51%) of the overall votes casted online, amounting to a 63.7% turnout.

As the election night unrolled, it became clear that this record turnout was accompanied by a massive liberal wave. R celebrated its fifth general election victory in a row, increasing its vote share from 28.9% to 31.2% (see Figure 2) and winning 37 out of 101 seats in Riigikogu. While R’s victory was expected, its magnitude exceeded even the most optimistic predictions. Yet, the biggest winner compared to 2019 was E200 that surged from 4% to above 13%, gaining 14 seats in Riigikogu. The social democrat SDE lost 0.5% of the votes and 1 seat polling at 9.3%.

The unequivocal losers of the election were EKRE and its potential associates K and IE. EKRE became the runner-up as predicted but lost votes and seats, obtaining only 16.1% of the vote and 17 seats, which was far fewer than expected considering that opinion polls constantly put them above 20% before the election. The biggest loser, however, was K: With 15.3% of the votes, it dropped below 20% for the first time in this century and lost 10 seats. While IE’s drop did not appear as dramatic, it also lost 1/3 of its parliamentary block size (12 to 8). Thus, the EKRE-K-IE trio received only 41 out of 101 seats in Riigikogu, burying all hopes of EKRE’s »conservative coalition«.

Figure 2. Estonian Parliamentary Election Results

The share of votes for the three smaller parties fell far below the 5% threshold. Yet the strong showing of the formerly completely marginal pro-Kremlin Estonian United Left Party (EÜVP) in the predominantly Russian-speaking districts in the East was one of the surprises of the election night. Despite not gaining representation in the parliament, their result did cost several seats for K, which traditionally had collected most of the ethnic Russian votes, and raised concerns about the alienation of the mostly Russian-speaking Ida-Viru county from the rest of the country.

Explanations

R’s success could, at a more general level, be attribted to them once again managing to succesfully define the central conflict of the election. While in the previous elections, R had strongly antagonized K on the basis of Estonian-Russian ethnic divisions and economic left-right issues, party representatives realized that the far-right populism represented by EKRE had become a better boogeyman against which they could mobilize people. EKRE, conversely, was for the first time competing for an election win and, unlike several other European far-right parties in a similar position, it failed to moderate its image to appeal to a broader voter base.

Yet, R’s strategy might have not played out so well had Russia not invaded Ukraine in February 2022. Just before the war broke out, opinion polls in Estonia showed EKRE as the most popular party, with K and E200 also very close to R in the ratings. It appears that the war triggered a »rally around the flag effect« that increased the support of the ruling party. Moreover, Prime Minister Kaja Kallas gained considerable attention in international media as one of the most vocal supporters of Ukraine and her tough stance on Russia earned her the nickname of Europe’s »Iron Lady«. This international fame converted into support at home, as Kallas was by far the most popular candidate for prime minister. Kallas’s popularity certainly helped R in keeping its momentum going.

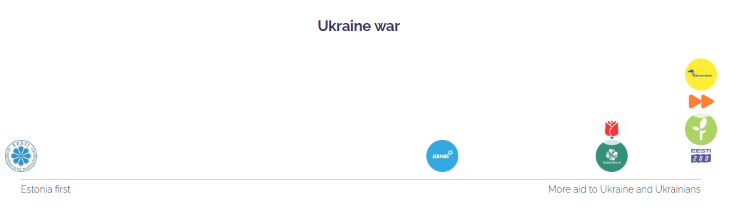

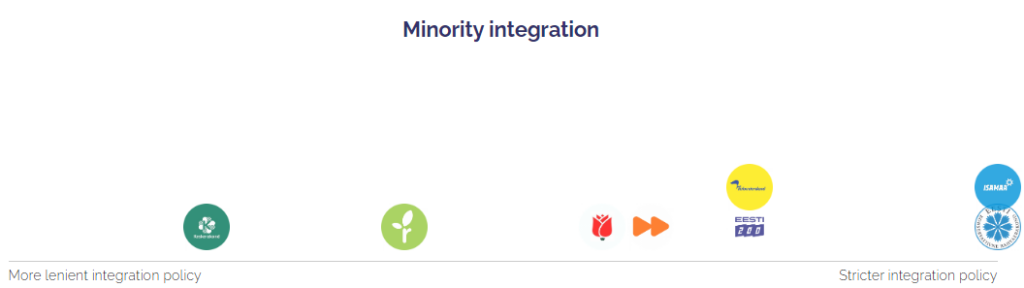

R’s two main rivals, EKRE and K, conversely, struggled with the Ukraine war and the issues that emanated from it. EKRE continued with its usual anti-mainstream style: it promised to significantly cut aid for Ukraine, stop receiving war refugees and even got into a public conflict with the leadership of the Estonian Defence Forces – one of the most highly trusted institutions in Estonia. Such an antagonistic approach did not work this time for EKRE, as a vast majority of Estonians support continued aid for Ukraine and accepting refugees. Thus, taking the opposite stance to the rest of the political field on Ukraine (see Figure 3) did not pay off. EKRE’s downfall was likely aggravated by a scandal that broke out a few weeks before the election when Politico revealed that Russia was scheming to support EKRE in the European Parliament election in 2019 to spread anti-Western narratives. K, on the other hand, took a more mainstream pro-Ukraine stance, which left some of their ethnic Russian voter base disaffected. Russian aggression also brought about a stricter stance on integrating the local ethnic Russian minority in Estonia, e.g. transitioning to a fully Estonian-language education system at an accelerated pace. K tried to advocate for a slightly more lenient stance on such issues (see Figure 3), but its messages remained unclear and did not seem to resonate with potential voters.

R’s landslide victory was even more remarkable, considering the massive inflation that hit Estonia in 2022, which reached as high as 25%. Both EKRE and K tried to push the economic well-being of the Estonian people to the top of the election agenda, but security concerns clearly outweighed economic issues. R promised to keep Estonia on its current track, emphasizing its experience and competence. Alongside having a very popular leader, this proved to be the winning formula.

Figure 3. Estonian Party Positions on the Ukraine War and Ethnic Minority Integration Issues

Aftermath of the Election

As the dust of election night settled, it became obvious that Kaja Kallas held all the cards with regard to coalition formation. Having the luxury of choosing between different alternatives, R made the most predictable decision and invited E200 and SDE to coalition talks. The three parties hold a convenient majority in Riigikogu, with 60 seats combined, and their policy agendas overlap on many issues.

While the liberal wing was preparing to form the government, EKRE refused to concede its election defeat and tried to cast doubt on the legitimacy of the e-voting procedure. But its protests did not resonate broadly and the only other party that chimed in with EKRE’s attack on the e-voting system was the pro-Kremlin EÜVP. All of EKRE’s and EÜVP’s appeals were dismissed by the national election committee and the Supreme Court of Estonia. EKRE’s chairman Martin Helme, predictably, was not satisfied with their explanations and continues to claim that the new Riigikogu is illegitimate.

K and IE, however, accepted defeat and entered internal leadership battles in the aftermath of the election. Both parties are not simply looking for a fresh image, but are at crossroads regarding their general political direction. In K, the choice is between the so-called »Estonian wing« and »Russian wing« of the party. The party has to walk a fine line between the two ethnic groups in order to stop their decline in both of these voter segments. IE, on the other hand, needs to decide whether it wants to further its alignment with EKRE’s hardline conservatism or take a course back towards the political mainstream. The choices that K and IE will make in the near future could have a large impact on what the Estonian party system will look like by the next general election in 2027.

Meanwhile, R, E200 and SDE reached a coalition agreement on April 10th 2023. As two out of three parties (R and SDE) have already been part of the previous government, it is clear that Estonia will remain on a similar political course. However, certain agendas will be expanded and accelerated with this more liberal party configuration. Green transition will be a high priority for this government, as illustrated by the creation of a ministry for climate. The new government also agreed to introduce same-sex marriage, despite R’s initial hesitancy to take such a step. Riigikogu has since adopted the agreed-upon legislation on June 20th, making Estonia the second Eastern European country to allow same-sex marriage.

On economic issues, however, things have been more heated and PM Kallas allegedly even threatened to form the coalition without SDE. Soon after the election, it was revealed that the state finances are in a worse state than previously reported, adding a frugal tone to the coalition negotiations from the start. R and E200 have emphasized that balancing the state budget is an important priority for them. Together with the increase in defence expenditure to 3% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (as also agreed in the coalition agreement), this implied that some painful decisions would have to be taken. Indeed, when the coalition agreement was revealed, it was met by a public outcry, in particular because of tax rises that took many by surprise. Criticism of the agreement was intensified by a surprisingly frank confession from Prime Minister Kallas that mentioning potential tax increases was avoided in R’s election campaign due to the unpopularity of such decisions.

Although the new government has also agreed to raise the minimum wage and put more emphasis on reducing regional inequality – another new ministry that was created is the Ministry of Regional Affairs – the agreement does not offer much in economic terms to those struggling the most. This is not surprising, considering the low popularity of classic left-wing parties in Estonia. As centre-left SDE holds less than one sixth of the parliament seats of the government coalition, they do not have much leverage to push for a more social democratic agenda.

The new cabinet of Prime Minister Kaja Kallas was sworn in on 18 April 2023 and it was immediately clear that there will be no honeymoon period. While trying to fast-track several unpopular or polarizing points of the coalition agreement through parliament, the government was faced with a large-scale obstruction by opposition parties, which has paralyzed Riigikogu for weeks. In addition to the generally unpopular tax rises, the plan to legalize same-sex marriage has sparked outrage and protests among the more conservative segments of society. The bumpy start of this new government is also reflected by a swift drop in R’s popularity in opinion polls.

The emotional tone of recent parliamentary and public debates indicates that the division between the liberal and the conservative camps is not only ideological, but also accompanied by hostile feelings on both sides. Thus, like in many other democracies, we are witnessing the rise of affective polarization in Estonian politics, which is a worrying and dangerous trend. While the polarization between the liberal wing and EKRE seems irreconcilable, the two other opposition parties have leverage to either deepen or alleviate the divisions in Estonian politics. Government parties, on the other hand, will need to show strong leadership in order to overcome the numerous internal and external challenges that loom in the near future. Although the 2023 election was a triumph for mainstream political forces, and it is almost certain that R will hold on to the office of prime minister until the 2027 election, it is certainly too early to say that the far-right populist wave in Estonia is crushed for good.

Andres Reiljan is a post-doctoral research fellow at the Johan Skytte Institute of Political Studies at the University of Tartu. He has (among other things) worked on the Voting Advice Application Valijakompass, from which the above graphs are taken.