- 02.02.2026

- Kategorie Literaturwissenschaft Geschichte / Archäologie Politik / Gesellschaft Forschung im Fokus

The ultima thule of dress reform

Find of the month: February 2026

by Eline Elmiger

For readers with a background in Scandinavian studies, Ultima Thule evokes the northern edge of the known world, sometimes identified with Iceland, Shetland, Norway, or Estonia, sometimes imagined as a mystical or unknown place beyond familiar geography. In mid-nineteenth-century newspaper discourse, however, the phrase could also appear in a very different register. In an article first published in the American New York Home Journal and reprinted in the Dublin Evening Mail, ultima thule does not denote a distant place at all, but a perceived social limit: the point at which a reform movement was thought to have reached its furthest conceivable extent.

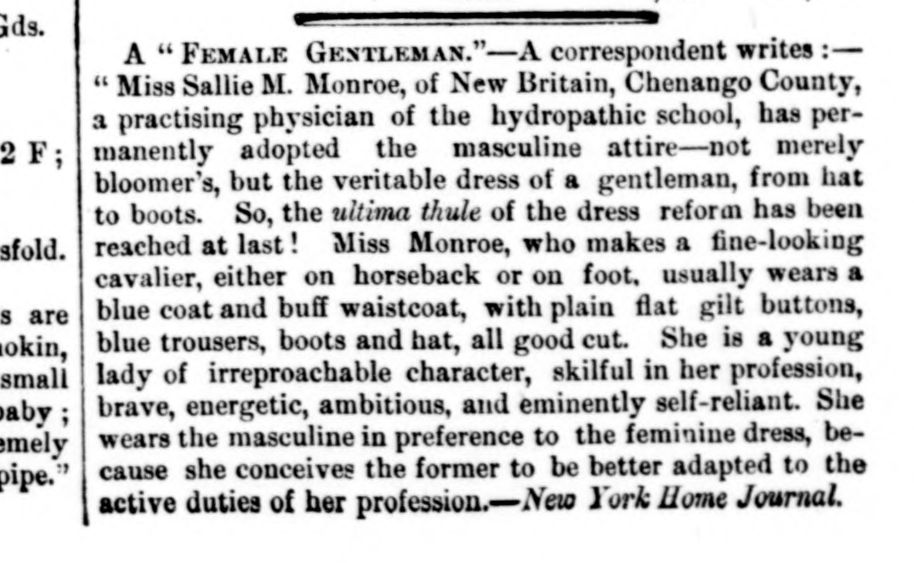

A “Female Gentleman.” – A correspondent writes: – “Miss Sallie M. Monroe, of New Britain, Chenango County, a practising physician of the hydropathic school, has permanently adopted the masculine attire – not merely bloomer’s, but the veritable dress of a gentleman, from hat to boots. So, the ultima thule of the dress reform has been reached at last! Miss Monroe, who makes a fine-looking cavalier, either on horseback or on foot, usually wears a blue coat and buff waistcoat, with plain flat gilt buttons, blue trousers, boots and hat, all good cut. She is a young lady of irreproachable character, skilful in her profession, brave, energetic, ambitious, and eminently self-reliant. She wears the masculine in preference to the feminine dress, because she conceives the former to be better adapted to the active duties of her profession. – New York Home Journal [Dublin Evening Mail, 01 October 1864, p. 3]

Several reform-oriented publications reprinted the paragraph without comment, among them the Banner of Light (a spiritualist newspaper, Vol. XV, No. 26, 18 September 1864, p. 5) and the National Anti-Slavery Standard (Vol. XXV, No. 19, 17 September 1864, p. 3), which was closely connected to the women’s movement.

To see why this example was framed as the ultima thule of reform, it helps to place it within the nineteenth-century dress reform movement. Led primarily by middle-class women associated with first-wave feminism, dress reform advocated clothing (mostly for women) that was considered healthier, more practical, and less restrictive than prevailing fashions. The bloomers mentioned in the article, wide trousers invented and promoted by the popular Water-Cure Journal, became a symbol of women’s rights in the 1850s, but were also often mocked, and their popularity fluctuated by region and over time. The “female gentleman” described here, however, did not wear bloomers at all, but an entire outfit of clothing conventionally worn by men. While dress reform challenged specific clothes and silhouettes, Monroe’s [1] presentation crossed into territory conventionally associated with male social roles and presentation.

Although the driving force behind the dress reform movement was not primarily the facilitation of physical labour (and women had long worked in trousers without societal approval, for example, pit brow women in the coal industry), the newspaper snippet explains Monroe’s clothing as chosen for professional reasons. Hydropathy (or water cure), now referred to as hydrotherapy, encompasses a range of approaches in physiotherapy, occupational therapy and alternative medicine. From the 1840s onward it was widely promoted as a cure-all, and hydropathic schools were often reformist spaces that, as noted above, even popularised bloomers.

What Monroe’s work consisted of in practice remains unclear, but the correspondent’s tone is admiring: Monroe is said to make “a fine-looking cavalier” and their character is described in strongly positive terms. This could be a form of legitimation for something that might otherwise have appeared transgressive. The remark that the “ultima thule of the dress reform has been reached at last” also appears to be approving rather than alarmist. Monroe was certainly not the first person described in the press as female to wear men’s clothing, and widespread changes in women’s fashion only followed in the 1920s, long after the Victorian dress reform movement. The newspapers that reprinted the paragraph did not add commentary of their own, either positive or negative. What is particularly striking here is the rhetorical use of ultima thule. Detached from its geographical and mythical associations with the far North, the phrase is used to mark an imagined absolute: the wearing of men’s clothing by a person framed as female, imagined as the furthest boundary of reform. This example, together with others from the same period, shows that ultima thule could denote not only distant places, such as the Isle of Wight (The Isle of Wight Observer, 12.07.1862), Normandy (The South Bucks Free Press, South Oxfordshire Gazette, London supplement for week ending 10.06.1865), Shetland (Dundee Advertiser, 20.03.1863 and 31.03.1865), but function more generally as a figurative expression meaning ‘the utmost’.

Thus, The Constitution, or Cork Advertiser (19.09.1863) writes that “reprovals are the ultima thulé to enforce unheeded remonstrances”, while The British Miner and General Newsman (31.01.1863) refers to having “reached the Ultima Thule of Scottish mining”. Such examples suggest that the expression was widely understood by mid-nineteenth-century readers.

Only one additional source relating to Monroe is currently known, an article by the New Orleans Daily Picayune (14. September 1864, p. 1, reprinted from the Utica Herald) titled “A Remarkable Water Cure. A Female Nurse Transformed Into a Man and Marries.” According to this article, Monroe treats a certain Mrs. Z., who has divorced her husband due to his infidelity. After travelling to New York and returning “hatted, booted, breeched, and bearded”, Monroe explains that “distinguished surgeons” had discovered Monroe’s “masculinity of sex” and that “she had been a man all her life without knowing it.” Monroe then marries Mrs. Z., which Mr. Z did not approve of. The (sensationalist and trope-heavy) newspaper article insists that “incredible as this story is, it is nevertheless true.”

Rather than clarifying Monroe’s life, this later report reframes it. What had previously been presented as a choice of dress and professional role is reinterpreted through medical discourse, effectively reclassifying Monroe within a binary model of sex. The narrative ‘resolves’ cross-dressing and same-sex marriage by asserting an underlying “true” sex, discovered and authorised by medical experts, a move that follows a common trope in nineteenth-century reporting. Notably, neither this article nor the earlier reports address the anti-cross-dressing laws that were in force in many U.S. cities at the time. Returning to the first newspaper article, ultima thule functions not as a reference to place, but as a lexical marker of extremity. The phrase does not mark the end of the world, but the edge of what could be said and done, while what lies beyond remains unarticulated.

[1] Note on names and pronouns:

As there are, within the scope of this ‘Find of the Month’, no known sources written by Monroe, and none of the surviving newspaper reports provide reliable evidence of Monroe’s self-identification with regard to gender, name, or pronoun use, I refer to this person by their surname throughout. Quotations from contemporary newspapers are reproduced without alteration.