- 06.12.2012

- Kategorie Politik / Gesellschaft

A republic without republicans? Statehood and identity in Finland since 1918

A guest contribution by David G. Kirby. The recent contribution by Michael Jonas on the ill-fated attempt to establish a monarchy for Finland in 1918 raises a number of interesting questions about the way in which the inhabitants of this newly independent country sought to define their constitutional identity. Seeking to secure a German prince as king of Finland may be construed as a consequence of the catastrophic events of the first months of 1918, when the newly-proclaimed country was plunged into civil war. The Whites had won this war with German help, and a broad coalition of conservatives was able to secure a majority in the rump parliament (Eduskunta) for a monarchy. The collapse of Germany at the end of the year not only killed any idea of a German sitting on a Finnish throne; it also obliged Finland to adapt to the notions of democracy which the victors of the war were now proclaiming. This meant the return to the political stage of the socialists, who succeeded in winning eighty of the two hundred seats in the Eduskunta elections of 1919. The return to parliamentary political activity of the socialists, and the growth in political representation of the Agrarian party – which had been firmly located in the anti-monarchist camp – effectively removed monarchism from the constitutionalist agenda.

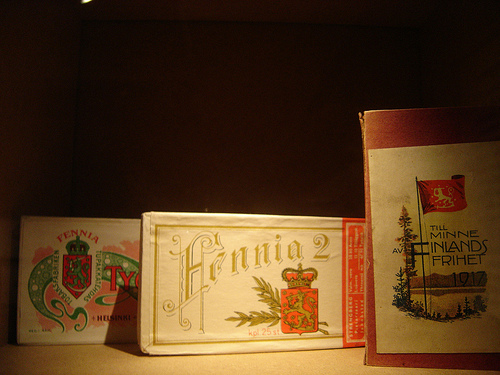

Monarchism, then, can be seen as a kind of foamy crest on the stormy seas of war and revolution, which vanished once the waves had subsided. Finland was to be and remain, as the declaration of independence of 6th December 1917 had proclaimed, an independent republic (riippumaton tasavalta). Words such as ‘republic’ or ‘republicanism’ have however never become embedded into the political vocabulary of Finland. Virtually all meaningful discussion of things political and constitutional uses the word ’state’ and its derivatives (valtio, valtiollinen). Why is this?

The first thing to note is that, in marked contrast to the other new states of north-eastern Europe, Finland opted in 1919 for a strong executive power vested in the presidency. This settlement prevailed until the end of the twentieth century, when a new constitution shifted the balance of power in favour of parliamentary government. It may be argued that conservative caution based on the experiences of civil war weighed more heavily in the minds of the Finnish constitution-makers of 1919 than was the case elsewhere, where the centre-left was very much in the ascendancy. But of greater significance is the fact that the Finns were also very conscious of constitutional continuity. The entire debate on separation from Russia was predicated upon the belief in the existence of a constitutional compact arrived at in 1809; the steps taken to detach Finland from the Russian connection in the autumn of 1917 self-consciously followed the Swedish Form of Government of 1772 as the inherited constitutional settlement; and the preface to the constitution of 1919 clearly envisaged this as a necessary renewal of a pre-existing constitution (valtiosääntö).

That inherited package of constitutional laws was strongly monarchical in character – indeed, the 1772 Form of Government was the keystone of Gustav III’s restoration of kingly authority and power in Sweden. It had allowed the Finnish elite to reach an agreeable working arrangement for the governance of the country under the Russian imperial sceptre, and when that working relationship began to break down in the latter decades of the nineteenth century, it afforded a solid foundation upon which to build a defence of Finland’s constitutional rights which, jurists such as Leo Mechelin argued, were being violated by the Imperial authorities. Thus, unlike the denizens of other newly-independent countries who had either little or no inherited constitutional tradition or who were unwilling to build upon any such inheritance that they regarded as alien, imposed or downright tyrannical, the Finns in 1919 felt able to create a new constitution based upon an existing corpus of laws and institutions. Those laws and institutions were created within the political context of a state or realm, and were adapted or carried over into the new republic.

This is fine as far as it goes: but one might ask, was there no enthusiasm for republicanism? Did the heroic images of the American or French revolutionary tradition not arouse the imagination of the people of this northern country? Given the strong loyalty of a significant section of the population for the social democratic party, which commanded an absolute majority in the Eduskunta during the crucial events of 1917, one might have expected at least some interest in democratic republicanism. But the one outward sign of such an interest, the draft constitution prepared by Otto Ville Kuusinen in 1918 for a future Finnish democratic republic, remained a dead letter. The Finnish socialist leadership were also nationalists, and they devoted a lot of time and effort in the spring and summer of 1917 in the pursuit of full internal sovereignty. The urgings of the leaders of the Russian revolution to set aside such matters for the constituent assembly to decide cut little ice with the Finnish socialists, who were more inclined to listen to Lenin’s advocacy of national self-determination as a necessary prerequisite for a future union of socialist republics. Republicanism was not a cause around which the Finnish left could rally in 1917, since those seeking to convert imperial Russia into a republic were also perceived as wishing to deny or limit the wishes of the borderlands to separate. Moreover, many of the issues upon which classic republicanism had been founded were either non-existent or had been largely subsumed within the Swedish/Finnish constitutional tradition.

What emerged out of the chaos of revolution and civil war, then, was the Finnish state, not the Finnish republic, and this proved to be something around which all Finns could rally. It was never divisive, as was the Weimar republic, and it did not collapse when faced with crisis in 1939, as had the Austrian republic a year earlier. It was Finland as a national independent state, rather than as a ‘people’s democracy’, that won the day during the turbulent 1940s. It might also be argued that it was the preservation of that state during the Cold War years that precluded the emergence of any kind of parliamentary republicanism that might have challenged the increasingly authoritarian presidential model. With the demise of the Soviet Union and the entry of Finland into the European Union, the balance has altered, and Finland has moved closer constitutionally to the ideal of ‘kansanvalta’, the democratic ideal embraced by the social democrats of 1917: but it remains in all essentials of political discourse a state, rather than a republic.

David Kirby is one of the most prolific experts on the history of Finland, Scandinavia and the Baltic Sea Region in the English-speaking world. As a Reader and later Professor, he taught Modern History at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at the University of London until his retirement in 2005. He is best known for his two-volume history of the Baltic World (published 1990 and 1995) and has published widely on Finnish history, his Concise History of Finland being his latest monography on this field.